Back in November ’13 I gave a talk at TEDx Jersey City about the game design class I’ve been teaching to children in northern NJ. Below is the transcript of my talk, including some of the images I used to showcase the work of my students.

See posts about individual classes →

Let’s Make Games: A Game Design Curriculum for Young People

A couple of years ago I went to a fund raising auction for my daughters’ charter school and was surprised to see numerous tables filled with children’s art projects, each one with a small basket to collect bids. I couldn’t for the life of me understand who would bid on an art project that wasn’t created by their own child.

Maybe the school had a young prodigy who could dramatically distill the essence and struggles of losing a dog or extolling the joys of space travel. More likely the projects were something the kids enjoyed making but were best displayed on their families fridge, not up for auction at Sotheby’s for Babies.

At the time I was working as a freelance online game designer for a children’s book author and illustrator and was supplementing my income by teaching drawing to children at local schools in Hoboken. I had returned to teaching after working 8 years at a major media company that produced content for young people. I had been creating online toys and games for youth but in those 8 years the only interaction I ever had with our audience was observing them on a tiny monitor while they did user testing in another room. Working directly with students in a classroom has opened up my understanding of how children’s minds work and has been rewarding in itself as I could observe and shape my student’s creative process.

I knew from my years of in art school and time spent working as a designer and programmer that there’s much more to developing artistic and critical thinking skills than just making work to display. It’s also important to learn to develop your own ideas, to work within grid and geometric structures, to imagine how your work will be received and used by others.

I wanted to develop a way of teaching art and creative thinking that engaged students with the world and didn’t focus so much on making pretty pictures. I wanted to bring some of my experience synthesizing various concepts into long term design projects. I wanted to instill in my students a sense of creative exploration and discovery while they create a product that will be used a shared by others. I wanted to move minds from thinking of art as being “Arts and Leisure” to “Arts and Science”.

For the past couple of years I have been developing a game design curriculum called “Let’s Make Games” that teaches elementary age students creative and design thinking. Our projects are meant to be played with, and children work within structured systems while also having the chance to write their own rules and participate with their friends and family in a play experience of their own creation.

The games I’m talking about are not video games but are physically crafted projects. They are board games, card games, mazes and puzzles. Students engage manual dexterity and craft while also exploring mathematical concepts of chance, probability, rule making, story telling and play. Our classes are collaborative and ideas can be shared freely among students during class time.

Game designer and teacher Eric Zimmerman’s states in his Manifesto for a Ludic Century that the 21st century will be defined by games:

We live in a world of systems.

The ways that we work and communicate, research and learn, socialize and romance, conduct our finances and communicate with our governments, are all intimately intertwined with complex systems of information – in a way that could not have existed a few decades ago.

For such a systemic society, games make a natural fit. While every poem or every song is certainly a system, games are dynamic systems in a much more literal sense. From Poker to Pac-Man to Warcraft, games are machines of inputs and outputs that are inhabited, manipulated, and explored.

I like to think that teaching game design gives children a way to create their own tiny systems, to help them build a structure of rules and procedures from their imagination and to see how things work within those limited structures. Game design instruction allows children to understand how art and design ideas work in the context of custom play spaces.

By creating projects that are to be used and played with others, they are able to iterate and learn how the decisions they make about rules and design affect the playability of their work.

INTERACTIVE STORYTELLING

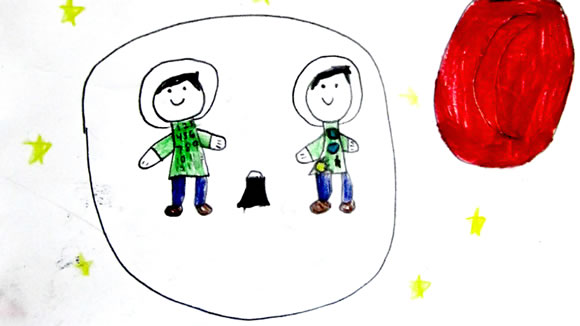

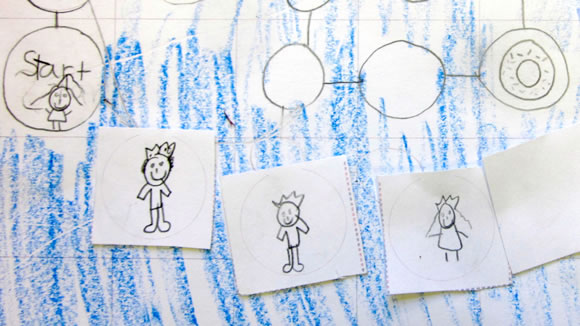

An empty board game is a blank slate for the child to create their own story and in class we follow a “quest” narrative. I start by looking at a story most of the children are familiar with: the Wizard of Oz. Here we have a story that easily translates to a board game. There are four player characters: Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Cowardly Lion and the Tin Man (or “tin can man” as some of my students call him). They are on a quest to meet the wizard and they have a straightforward path to follow. This is one of my favorite parts of class because I wind up with a room full of little kids looking at each other and saying “Follow the yellow brick road? Follow the yellow brick road!”

The children develop a theme for their quest and work within this theme in creating their characters, dangers and rewards. Once the child has settled on a theme there’s a great creative outpouring as they imagine all the possibilities they can explore within their quest. This is an important activity for creative thinking because it focuses the mind into one area. From an entire world of general ideas there is a narrowing down to a specific environment, and this opens up a new world of possibilities for exploration based on a theme.

GRIDS & POLYHEDRA

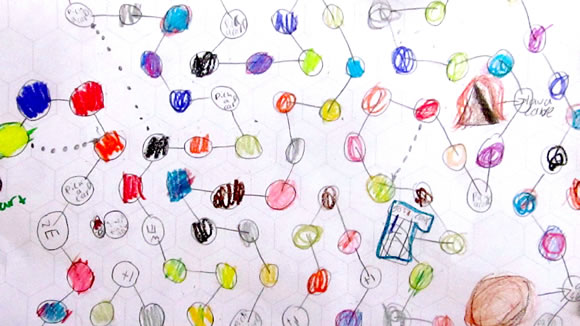

While the constraints of a theme help focus the mind, the grids we use to build our games help guide visual balance. Our board games are constructed on gridded paper, square and hexagonal. These foundational grids give students an ability to break their courses into small pieces and work with evenly spaced elements. The semi-visible web of spaces allows every game to have a consistent architecture but also allows organic expression within its boundaries.

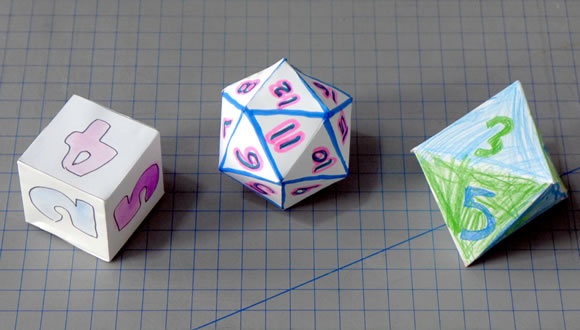

One of the central elements in our board games is the dice roll. We construct the die ourselves and this allows everyone to experience the geometry of solid structures first hand. While 6 sided die are the standard in most game I introduce a variety different geometries in addition to the cube: tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron. By using different sided die the class can play with and understand how number and probability affect how their game is played. Using 10 sided dice on a small board can make for a much quicker game than using 4 sided die and students can see how chance and probability work in the context of their game boards.

Once they count each of the spaces on their boards they can see how quick or slow their game will play based on how many spaces they can jump on each roll. They can then enhance the game with landing places that jump the player forward or back a chosen number of squares. There will always be one child who takes a thrill in making a square that pushed the player back 3 spaces, only to land on a square that pushes them forward 3 spaces, thus sending them back 3 spaces, and on and on in an infinite loop.

CREATING RULES

Within each of our projects students are given freedom to see how adding complexity changes how fun the game is. Within the specific game structure the students are able to write some of the rules themselves. Too often we place kids in situations where the rules have been written long ago or we structure activities that the child is forced to conform within. While it is important to learn these traditions and structures, when they are used exclusively it can stunt and restrict creative thinking.

I remember playing kick ball in elementary school and we developed rules on our own that were dependent on how many kids had been called home for dinner. You’ll have a tough time covering four bases when you’ve only got three kids on your team, and one of them is the pitcher. Part of the fun of the game was developing ways to keep playing while dealing with changed circumstances. Chris has to go home for dinner and now the teams are uneven? Let’s switch to a permanent pitcher who’s neutral and keep the teams even.

This kind of flexibility and resourcefulness is important to nurture in kids if they are going to grow up and work with other people and changing circumstances. By creating their own game rules the children are empowered to manage a small little world of their own design and shape how other children will play their game. In making rules themselves they are better able to appreciate the rules they encounter in their daily lives.

CRAFTING & VISUALS

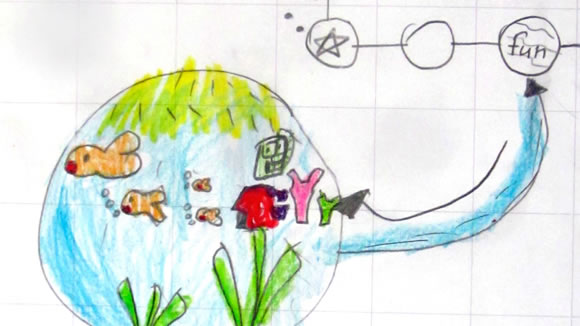

As much as I talk about structure and story, in the end we’re there to make stuff and drawing and coloring become an important element of our classes. In some games the visual aspect is crucial to the game itself, such as this halloween themed game where each square has a corresponding color on the 4 sided dice. The children are able to express themselves in the decoration and construction of their games and work with materials and craft.

Within the confines of the game project each child is able to concentrate on their own unique visual language. Symbols and their use are important components of visual communication and our games offer opportunities to create sets of icons and pictures. By creating their own visual icons students learn how they can use form and color to communicate and heighten the play experience.

PLAY & ITERATION

One of the most important aspects of game design is actually playing the game and it’s here that students can see their ideas put into practice and enter into the world they’ve created. I would venture to say that there aren’t too many children sharing each others homework assignments in their free time, but once they’ve created a game it begs to be shared and played with. I encourage the kids to play their games as they make them and to consider how the decisions they make in the creation of the game will affect how fun the game will be to play.

For example, I always have at least one child in class who insists on making a space on the game that essentially eliminates the player who lands on it. Whether they’re eaten by a shark or fall into a pit there is a deathly square that knocks the player out of the game. I can’t figure out which is worse; when they place it at the beginning of the game so the player is out after their first roll, or at the end, when they’ve invested time in playing only to be dropped out.

It’s important to have the student put themselves in the shoes of the player who just lost. When I point out to the child that this black hole of a space will frustrate who ever lands on it I sometimes get an evil grin and sinister chuckle. After a bit of thought and playing through the board a few times they begin to realize that as much as they may wish to torture their players, no one is going to like the game if they’ve been sitting on the sidelines after getting knocked out in the first 10 seconds of play. Their sense of empathy with the games users can encourage them to revamp what they’ve done and create a game that’s more fun for everyone.

In the end I may have learned as much, if not more, from my game design students than they have from me. I’ve enjoyed seeing the stories they’ve told and the creative ways they’ve colored outside the lines of the visual and theoretical grids I’ve set up for them. Through my classes I hope to impart in students an understanding of design and creative processes, to have them create work that facilitates play, that lets them write their own rules and make projects that they can share and play within.

Understanding the mechanics of games lets students develop higher order creative skills that can allow them to understand many of the complex structures of our lives. It’s an alternative form of teaching math, story telling and art and in the end, it’s a lot of fun.